We are exploring how Solid – a proposed set of conventions in development by a project run out of MIT CSAIL – and the hi:project are mutually supportive.

Solid decouples the app from the data, and the hi:project decouples the interface from the app. In other words we move from one app working exclusively with and effectively having sole domain over your respective data, to having numerous apps from many vendors being able to work with your data with greater privacy (Solid), to your own interface onto and into your data with assured privacy and transformed usability and accessibility (the hi:project).

Here’s a guest post by Andrei Sambra, a Postdoctoral Associate at MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory. Originally published here.

This entry is meant to be the first one in a series of posts that introduce Solid, our new disruptive solution to re-decentralize the Web – a project lead by Prof. Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the World Wide Web.

The project aims to radically change the way Web applications work today, resulting in true data ownership as well as improved privacy. How’s that for an elevator pitch? 🙂

Before getting into the technical stuff, you need to understand why decentralization is so important for us at this time. To answer this question, we must first explain why centralization is bad.

Centralization is a cheap and easy point for regulation, control and surveillance – your information is increasingly available from “the cloud”, an easy one stop shopping point to get data not just about you, but about everyone. Centralization is also easy – why waste time and money (as a small business) investing in a decentralized product, instead of going with some off-the-shelf tech stack? While these may be valid points that may eventually be addressed, the end result is that we all pay a price – whether it’s losing your data or actual money. This reminds me of a funny (but sad at the same time) quote that goes like this:

“A pig on a farm gets free food, shelter and health care. If you’re not paying, you’re the product!”

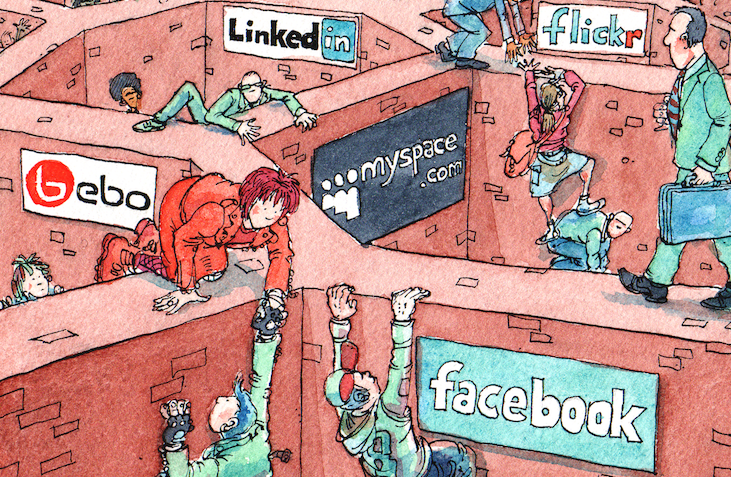

I’m sure many of you are familiar with this picture from the Economist. Back in 2008 (!) it was used to describe the walled gardens, or data silos, as other people commonly refer to them. Even after all this time, it depicts our current reality with amazing accuracy. Most of you probably see people trying to escape by climbing these walls around common services like Facebook and LinkedIn. What you may not notice is that there are no doors or even ladders in this picture. The data silos make no effort allow people to get out. We commonly call this practice vendor lock-in.

Once you start using a web site or application, you become trapped. Sure, some web sites offer integration (through APIs) or bulk exports, but ultimately the data you generate through them stays with them. Integration does not mean that using each service that is integrated is done in a completely private way. On the contrary, they get even more data on you, that they wouldn’t otherwise. Also, exporting your data doesn’t guarantee that you can easily reuse it later – we all know what a pain even migrating a database can be.

Let’s put things into perspective…

If you think Big Data is big, think again. With the Internet of Things (and the coming Web of Things) products hitting the market over the next few years, we will have to start talking about HUGE data. Everything we do, starting with the objects we touch, our health data, the advertisment panels we glance at, everything will be stored somewhere. Soon enough, software alone will decide whether you get a loan, a job, or maybe ultimately make life and death decisions. You may think that this is still early and/or it will never happen to you any time soon. Think again…

Two years ago, there was a paper published by Robert Epstein and Ronald E. Robertson in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2014, called The search engine manipulation effect (SEME) and its possible impact on the outcomes of elections. Their experiments showed the following:

- biased search rankings can shift the voting preferences of undecided voters by 20% or more

- the shift can be much higher in some demographic groups

- such rankings can be masked so that people show no awareness of the manipulation.

We’re fighting a war today that is far from being conventional. We’ve seen how public opinion can be easily influenced by abusing search engine results, or social networks. A single tweak in the search algorithm can make or break history. In the United States, half of the presidential elections have been won by margins under 7.6%, and the 2012 election was won by a margin of only 3.9%. That’s well within the 20% margin.

We’re fighting a war today that is far from being conventional. We’ve seen how public opinion can be easily influenced by abusing search engine results, or social networks. A single tweak in the search algorithm can make or break history. In the United States, half of the presidential elections have been won by margins under 7.6%, and the 2012 election was won by a margin of only 3.9%. That’s well within the 20% margin.

Powerful groups will decide who gets privacy and security and who doesn’t. The next billion Web users will come from countries that don’t have a bill of rights, so who’s going to protect their free speech? The Brazilian gov introduced the “the internet’s bill of rights – Marco Civil Da Internet” last year, paving the way to net neutrality. But, people have noticed that it lacks a comprehensive data-protection law, and this makes Brazilians’ data vulnerable to prying eyes. It’s very important that whenever new regulation is proposed, the process must be transparent, resulting in law that works in the best interest of the people as a whole.

OK, so you know what the problem is. What can we do about it? I think we need to start by breaking down the problem, and fixing one thing at a time.

First, we need to aim for user-centricity. Right now, when a new service is launched, if we want to avoid logging in with Google or Facebook to use it, then we need to sign up. Every time we signup, we have to re-type in the same data over and over again. Sometimes we spend years pouring a lot of data and time into the same service (think Twitter or Facebook), but what if tomorrow it shuts down or it is bought? What happens to all the data we created there so far? Sure, we might be able to download some of it, but what can we do with it? Where else can we use it?

The solution is a user-centric approach, in which data is stored under our control, in a place of our choosing. And when someone wants access to our data, then we decide who gets to access it and on what grounds, but on our terms. This is the path Solid takes.

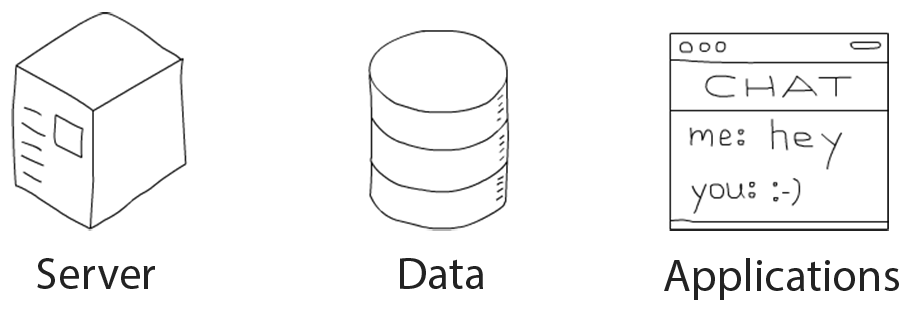

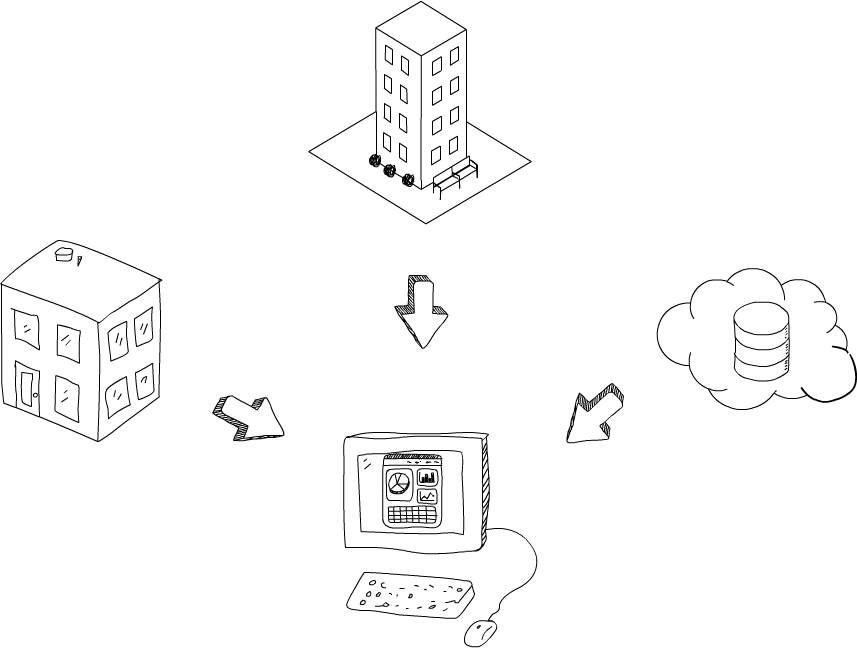

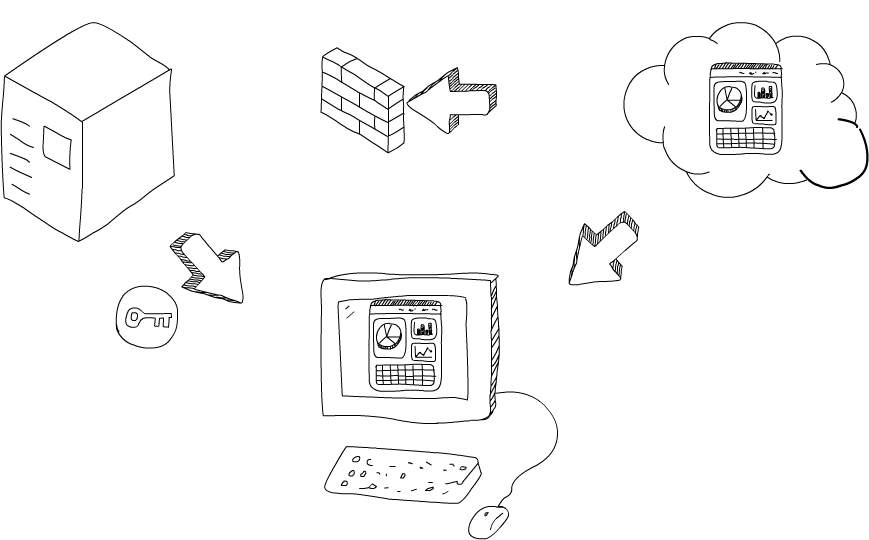

From a technical perspective, we can break down the problem into multiple steps. The first step is to decouple the applications from the data they produce, and then to decouple the data from the actual storage server.

This means that applications and servers are interchangeable, and they can be swapped without impacting the most important part – your data. It’s all about freedom of choice. Here are some immediate advantages offered by Solid:

- users will be able to chose what applications they want to use based on their personal preference, instead of being stuck with what application (i.e. UI/UX) the service provider offers

- developers will be able to fork (open source) software and add new features, or even create new software from scratch, but the new software will act as a thin UI layer on top of the same data. This is not completely unheard of. In fact you’re actually doing it already – have you ever installed a different Twitter client on Android or iOS? The data (i.e. tweets) is the same, but the UI is sometimes different. However, Twitter’s API limits the number of features you can add. Solid doesn’t – you can improve the existing schema, add new data types, you name it!

- user-centricity also benefits business, as they will be able to reuse data which is generated by other services.

So yeah, in the end everyone wins.

Next, let’s talk about where the data is stored. Solid applications can store data on different servers, in different locations. It could be on a raspberryPi at home, on your work server, or even with a cloud provider. Each of these options has its own pros and cons. The important thing you have to remember is that you should have the freedom to decide where you want to store your data, depending on your needs.

Let me walk you through how Solid apps work. Say you want to load a Web app from some place (in the cloud). “Running” the app simply means you just need to load the Javascript, HTML and CSS files.

Next, you introduce yourself to the app so that the app knows how to follow its nose and get to your data servers. At this point, the app fetches your data from your server(s), in a p2p way, over a secure TLS connection. During all this time, the company who made the app has no idea who you are and as well as no access to your data. Sure, it could turn out the app is built so that it sends data back to the mothership. This is not a new problem, as we often see news of apps being pulled from the popular app stores even after passing their rigorous tests.

In any case, we hope that soon enough we will see concepts like “benevolent apps” or “respectful licenses and terms of service” emerge. Code audits and reviews will also help weed out the bad apps.

In the next post, I will try to go over some more technical details, and present the architecture. If you’re too excited about Solid and can’t wait, you check out our Solid organization on Github.

Image credits

- The Stata Center, by Mareklug, Wikipedia, with CSAIL logo overlaid

- Social Networking Sites as Walled Gardens, by David Simonds, The Economist, 2008

- Tag cloud, Wikipedia

One thought on “Solid – an introduction by MIT CSAIL’s Andrei Sambra”

Comments are closed.